"Alchemised": A Heartbreaking Phenomenon That Might Challenge You Deeply

I am not a fan of dark fantasy. Too much extreme violence and pain. Yet, I've read so many glowing reviews of this book, I had to give it a go. Here are some deep questions it sparked for me.

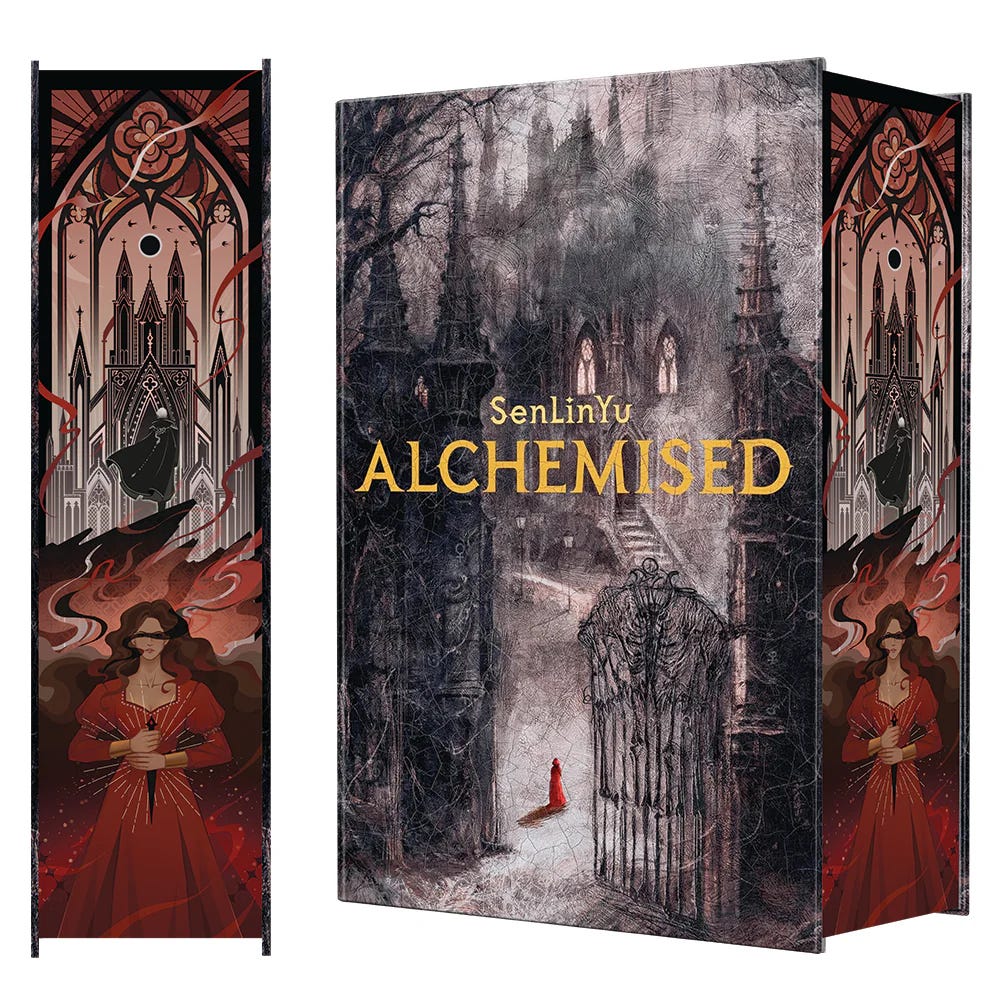

If you are a fantasy reader (and even more so if you are a Harry Potter fan), you are likely to have seen “Alchemised” pop up in your news or social media feed lately. I first came across it as I read a mention of “Manacled”, a massive 900-page Harry Potter fan-fiction book written in instalments during the pandemic by SenLinYu, exploring an alternative ending in which Harry Potter dies and Hermione Granger and Draco Malfoy fall in love from opposite sides of a war that the Death Eaters have won. Apparently, there is a whole world of Harry Potter fans exploring these alternative endings to the story, and apparently, “Dramione” stories are plentiful. Who knew that so many people wondered what might have happened if Hermione loved Draco?

I have never read Manacled, which, as far as I know, is no longer available online, but I do know that SenLinYu, an author who identifies as non-binary, wrote some 900000 words on their phone notes app during their baby’s naps through the Pandemic. Their version of the Dramione story was so successful that it was downloaded 20 million times and led to them rewriting that story in a whole new universe, with another magic system and different enough characters that it warranted being seen as an original novel and published by a traditional publisher. It broke records as a fantasy debut, it’s being hailed as the most successful debut in years, and it already has its own movie deal.

So, is the hype worth it?

That is a tricky question because, as with any piece of art, the beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The trouble is, Alchemised has to be one of the darkest books I have ever read, and there is very little in it I would consider ‘beautiful’. It’s also a monster of a book at 1000 pages (one of those times I’m grateful I buy most of my books on Kindle). When I first picked up the book, the opening scene was so horribly painful that I put it down and decided it wasn’t for me. Then, I gathered my courage and re-started, I read it in a weekend - almost swallowing it whole quickly, like you would a bitter pill. But why put yourself through it? Once started, I somehow felt compelled to keep reading, and I really would like to explore this question:

Why would we read books that cause us pain?

Part of the question I’ve come to is that we read books that captivate us, that keep us wondering what will happen next, that keep us clinging to a thread of hope for characters we end up caring deeply about. This definitely happened with this book for me, but there was more. I realised the author seems to be pushing the limits of a scenario of how much cruelty and how many atrocities are humans capable of committing in the name of a quest for power, greed, or protecting their own attachment to a dogma and, most terrifying, how cruel can humans be in the name of love?

I think it takes a lot of courage for a writer to throw themselves so deep into the bowels of human darkness. There is almost no glimmer of hope for these characters for 900 pages, until, at the very end, they find some light. And perhaps the main reason why I stuck with this book is that I feel we are traversing such a dark time in our history as a species and I’ve felt so hopeless so often over the past year or so that somehow I’ve both drawn a parallel between SenLinYu’s depiction of life and love during a war and the hopelessness of no end in sight, and the hope of still, somehow, seeing a way out.

Also, interestingly, after I put myself through the pain of contemplating all that darkness they depict - which closely mirrors real world conflicts happening in the world right now (and the indifference of those reading about that suffering but doing nothing to stop it) - I came on the other side with a sense of hope and agency, with the question of ‘what is in my power to do to make the world a little bit better?’. It seems you sometimes have to swim in a pit of hopelessness to put your own into perspective.

So, what is this book about? What did I like, not like, and what moral questions did it leave me with?

If you’re intending to read this book, beware that the rest of this article will contain spoilers.

The book is split into three parts, which focus on different time periods in the story. It follows an alchemist and healer, Helena Marino, in the aftermath of a devastating war in the city-state of Paladia, where her side, The Order of the Eternal Flame, lost, and the ‘bad guys’ led by the evil necromancer Morrough have won. Helena wakes up a prisoner, having been kept in stasis for over a year, and with a couple of years' worth of memories missing. She used to work in the Order’s war hospital and has clear memories of her childhood friendship with the Order’s hero and religious figure, Luc, who was killed in the war, but she cannot remember the last months of the war or how everyone died, and she was captured.

As the necromancer’s people discover Helena’s memories have been altered and suspect she is hiding an important secret, she is given as prisoner to the High Reeve, Kaine Ferron, the High Necromancer’s right hand (and lead executioner). He is supposed to break her mind and find out the missing secret (which he attempts repeatedly), and do so in a way that doesn’t kill her before she reveals it. The first part of the book documents Ferron’s abuse of Helena as part of his mission to find her secret, interspersed with strange acts of ‘kindness’, but also with horrific acts such as Handmaid’s Tale-type ritualistic r**e with the purpose of having Helena produce an heir as a new suitable body for the immortal Necromancer’s soul. Even though this act was dictated by the High Necromancer, and it’s clear neither character is consenting, and also we find out in part two that there is a pre-existing relationship between the characters, none of this sweetens the horrific nature of such an act.

Can you hurt the person you love as a justification for protecting them?

Are such hurtful ‘protective’ choices we make in relationships for the other person, or in fact, are we protecting ourselves from the pain of seeing them suffer or losing them?

I find this one of the most compelling and difficult questions in this book. Interestingly, it’s something Helena herself asks late in the book after both of them have caused each other incalculable suffering with the intention of protecting each other. I’m still sitting with this question - not only when it comes to love relationships, but also parenting, friendships and any other meaningful relationship.

How do we love others as they need to be loved?

The magic system in this book relies on the idea of alchemy and the power of manipulating metals, but also fire and even human bodies and minds. Some forms of alchemy are honoured (like metal work) and some have been shunned, like ‘vivimancy’ (which is what Helena’s gift was) - the ability to manipulate another human’s body or even resurrect the dead. The now defeated “Order of the Eternal Flame” had been not just the ruling class of Paladia, but also the founders of the largest alchemy academy on the continent, promoters of knowledge and learning but also upholders of religious dogma that deemed certain forms of alchemy as ‘superior’ to others and emphasised a life built upon suffering and sacrifice in service of ‘purification of the soul’.

Of course, things are not as they seem, and in part 2 of the book, we discover that Kaine Ferron is more than the villain he seems in the first third of the book. There is a backstory to Helena and Kaine’s relationship that we get to explore, which is also fraught with heartbreak, against the backdrop of a ruthless war where she gets to use her ‘impure’ vivimancy gifts to heal the Flame’s soldiers. The hypocrisy of a regime that maligns certain talents (or people) while also ruthlessly using them to achieve its aims is not lost on the reader.

In part 3, Helena and Kaine get to search for an end to the conflict and a happy ending for their relationship, two outcomes that seem mutually exclusive. Now, I’m a sucker for happy endings, and I would have been devastated if this book didn’t have one. On the other hand, the fact that it did have one opened up some profound moral questions.

Kaine Ferron is, objectively, a mass murderer. There are so many moral questions here!

Does the fact that he himself is a victim - tortured and coerced in the most inhumane ways - justify his actions as a perpetrator against myriad people?

Does his obsessive love for Helena justify killing thousands of other nameless, faceless people in her name? Does the fact that he doesn’t enjoy killing make it less gruesome?

Does his love for Helena justify the horrible things he does to her in Part 1 of the book, under the pretence that they are being watched and she could not remember who he was, and for some reason (which remains unclear to me), he can’t just simply stay out of sight, tell her the truth and try to help her remember instead of taking her amnesia as a fact and playing the role of torturer that had been bestowed on him?

Can his love for her (and for his mother) excuse his inability to seemingly feel any shred of compassion for any other person apart from those two? What makes a villain? Does loving just two people to the extreme redeem someone from hurting the rest of humanity?

I confess I was deeply touched by the tragic romance unfolding through this book. The way these two characters fall in love in the first place is again rooted in trauma and a ‘lack of’ rather than any healthy attraction to a possible love match.

By the end, when Helena and Kaine finally get the dream of peace they have worked so hard for, their trauma doesn’t go away. And I did appreciate the author’s honesty in acknowledging that fact. The unhealthy dynamics in their relationship still need careful management. What I didn’t appreciate was how glossed over that fact seemed to be - more of an afterthought, bathed in the beautiful light of a new beginning, rather than a stark reality worth investigating closer. When the war outside is over, the one inside rages on.

Through this book, Helena’s friendships, in particular her friendship with Luc, are equally tragic. There is something idealised about this foreign girl being chosen by the country’s revered heir as his best friend, and then her inexplicable and almost obsessive devotion to him (somehow a sign of aberrant gratitude for ‘being given a chance’), which comes part and parcel with an unwillingness to tell him any hard truths, even when he’s making awful decisions because of his own deluded views. And she is not the only one of Luc’s friends who does that - protect him from truths that could save them all. So this begs other questions:

What is friendship about then?

If your best friends systematically lie to you, keep you in the dark, coddle you to save you from discomfort (or to preserve a collective narrative whose cracks are clearly showing) - is that still friendship?

If you are a human in power and there is nobody around you to tell you you are wrong, deluded, fighthing for a lost cause or needing to change your tactic and question your beliefs in service of the higher good - what kind of a leader are you? Is it a failure of leadership to not have any dissenting voices around?

This brings me to the more systemically relevant conundrums in this book. We are looking at a world where the ‘good guys’ are revealed not to be that good and pristine. The ‘good guys’ have built narratives around their own superiority and their ‘divine right to rule’ that end up blinding them to their own shortcomings and impairing their ability to keep growing and adapting.

Their original positive intentions (e.g. to build an alchemy academy and make this craft available to all) are perverted by rigid rules (e.g. certain alchemical talents are superior to others, or certain students can only study up to a certain level because their ‘work class’ background doesn’t justify more opportunities) or by religious dogma (e.g. waiting for a ‘higher power’ to intervene on your behalf if only you ‘earn’ that divine intervention through being exceedingly ‘good’, ‘pure’ and ‘self-sacrificing’ - even when that self-sacrifice becomes obtuse and self-defeating).

And the ‘bad guys’ have pretty decent justifications for the impulse of pushing back against the ‘good’ - they feel unseen, unvalued, unable to bridge the increasingly terrifying chasm between them and ‘the elites’ whom they come to despise. What starts as legitimate concerns and protest is then hijacked by a very charismatic, truly psychopathic (pure evil) figure who weaponises people’s fears and anger at those in power, leading to war and ultimately a regime of terror that hurts everyone and only benefits the narcissistic leader and their camarilla. Does this remind you of real life at all?

This, to me, opens up a final series of questions:

How can we, humans, use our power wisely? How can we build tolerance for having our most deeply held beliefs challenged without shutting down the other’s viewpoint, nor feeling like traitors for simply considering another perspective?

How can we keep listening to each other, even when we are on opposite sides of the ideological divide?

How can we look beyond our narrow spheres of interest - the people we love and care about, our community, our culture - and acknowledge the existance of other ways of being in the world, without feeling threatened by them?

How do we balance our individual concerns with broad societal concerns?

If you’ve read this far, I hope you already know what you feel like doing next - either jump into it or give it a pass. I’d rather not make a recommendation. This book is not an easy read. Unlike Strange the Dreamer, which I recommended wholeheartedly in my previous review, this book comes with a host of trigger warnings (do make sure to read them before you start!), it contains some very heavy material and will raise some very uncomfortable questions. If you are willing to have your mind challenged in this way, I do hope you read it (I don’t regret doing it!), and I’d love to hear your take on it. I for one am grateful for the reflections it sparked.

Why subscribe?

Subscribe to get full access to the newsletter and publication archives. I’ll write infrequently, when inspiration strikes me. It might be writing about writing. Writing about learning how to write. Writing about books I love (all fantasy here, the nerdy/academic stuff you can find on Alis’ substack). Writing about the unravelling that comes with doing someting for the very first time in your mid-life and relishing every moment of it, even the hard ones! Join me and let’s see where it leads us!

Stay up-to-date

Never miss an update—every new post is sent directly to your email inbox. For a spam-free, ad-free reading experience, plus audio and community features, get the Substack app.

Join the crew

Be part of a community of people who share your interests. Participate in the comments section, or support this work with a subscription.

To learn more about the tech platform that powers this publication, visit Substack.com.

Thanks for reading Bianca Wolff! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.